I've been wrong about the meaning of Meritocracy, and for good reason, there are many different definitions—the term has been used as a pejorative, as an aspirational term, as a definition of a government, and as a general way of allocating credit to individuals. But I understood it as this:

A society where a person's rewards reflect their efforts (merit)

For me this had been an aspirational definition, an ideal that cannot ultimately be reached, as individuals are afflicted by myriad confounding factors that make this impossible. Nevertheless, I feel this is the sort of society we should try to foster, where if someone wants to improve their life, they can do so simply be trying harder, if someone does not want to improve their life, they don't need to. This is the sort of world I'd like to live in.

From this perspective, the tension in society and politics is between two sides: one that is working to make the world more meritocratic—by levelling the playing field, and another that wants to claim that the world is already meritocratic—so we should reward people based on what they achieve as if it is a direct reflection of their effort.

This means, from one perspective, individuals who are not doing well are looked at with sympathy, and from another perspective, they are judged critically or, as Alain de Botton points out, they are described as either "unfortunate" or "losers"

"In the middle ages, in England, when you met a very poor person, that person would be described as an "unfortunate"—literally someone who had not been blessed by fortune, an unfortunate. Nowadays, particularly in the United States, if you meet someone at the bottom of society, they may unkindly be described as a "loser"."—Alain de Botton

To my mind, people who perceive those who are not doing well as "losers" because they assume we already live in a meritocracy (as I've defined it) are delusional. As mentioned, we cannot achieve a perfect meritocracy, so assuming we already live in one makes no sense.

But, it's even more complicated than this. Because my definition is not what is generally meant by "Meritocracy" at least not all the time (it slips—we'll get to this). What is generally meant is:

A society where a person's rewards reflect their achievement (merit)

You'll notice the two definitions are the same, except for how "merit" is defined. In my definition, merit is equivalent to "effort", in the general definition it is equivalent to "achievement". And this is because "merit" literally means:

The quality of being particularly good or worthy, especially so as to deserve praise or reward.Our assumptions about what is worthy of reward (effort or achievement) are a key component in the definition, making its relationship to meritocracy circular.

A society where a person's rewards reflect what is worthy of reward (merit)

You see that the definition is self-referential!

So, to avoid this ambiguity, from this point forward, when I use "meritocracy" I am referring to the achievement-based definition, and I will use the, admittedly clunky, "effortocracy" to refer to my earlier effort-based definition, and let's see how much trouble we can get into.

From a meritocratic perspective, university applications should be entirely based on marks, the level an applicant has reached at the point of time when they apply. No attention should be paid to how far they have come to reach that point, what hurdles they have overcome, how much effort it has taken.

When defined like this, we generally do already live, by default, in this sort of meritocracy. People are naturally rewarded for achievements, regardless of how much effort it took. But this doesn't mean that this is in any way a fair, or equitable model for society. For instance, someone born into a fortune has a greater capacity to achieve things, in some respects they can achieve things just by buying them.

They can achieve broadening their mind through unrestricted travel, they can achieve a university education from a prestigious university or they can financially support a cause they care about. All of these achievements have material benefits for them, and they receive praise and reward accordingly. But these are achievements that are not available for people with no money. And this is not restricted to financial advantages; genetic and environmental advantages, natural talent and early opportunities are unevenly distributed also.

"… differences of talent are as morally arbitrary as differences of class."—Michael J. Sandel, The Tyranny of Merit

As a utilitarian, I don't want to discount the importance of achieving real outcomes in the world. Getting educated, becoming more cultured, and donating to meaningful causes have real benefits for the individual and the collective.

They have value—they just have a value that is already appreciated by default. This is why it's important to consider effort, which might be difficult to quantify, or to reward systematically, but which comes with some worthwhile benefits.

There are three reasons why we might consider aiming at an effortocracy:

- It's fairer

- It's a better predictor of future success

- It will access more human potential

First of all an effortocracy is fairer, by definition. My definition of an effortocracy is motivated by an assumption many of us share that fairness is about equal opportunities, not in a narrow sense—in that we all technically have the same legal rights—but in the deep sense that it is unfair if someone doesn't have to work as hard as someone else for the same reward. Children understand this implicitly, especially when they are on the receiving end of the unfairness.

As we mature we learn that this is not realistic, and that the world is unfair, and that regardless of this unfairness, you are largely responsible for your own goals in life. This is not necessarily any growth in wisdom on our part, but rather a resignation about, or a justification for the situation we find ourselves in. It's a way of coping, or a way of allowing us to ignore the injustices faced by those less fortunate than ourselves. We can even employ cynicism, implying that notions of fairness are idealistic, and create bogeymen that these sensibilities are on a slippery slope to communism. But I think the wisdom of our inner child would tell us that greater fairness is a worthwhile end in itself.

On the subject of juvenile wisdom, I asked my daughter recently about whether she thought people should be judged based primarily on their character or by what they contribute to the world—I was testing her intuitions around virtue ethics and utilitarianism. Her answer was sort of profound, she said…

Character, because people have different opportunities to do good in the world.

She was making the point that someone might be really good but have limited means to achieve good outcomes, whereas someone else, who has vast means might be able to do an outweighed good without actually needing to be a particularly good person.

Again, I don't want to discount the utilitarian value of good done by the high capacity person, donations have the same value regardless of the virtue of the giver. My daughter was pointing to the predictive value of the assessment, the person of good character is more likely to continue doing good. The example of Elon Musk immediately sprang to mind, a person, that for about a decade, generated tremendous good in the world, but at the same time demonstrated significant character flaws. It turns out flaws like crashing his McLaren F1, numerous failed marriages, psychologically torturing his employees, being painfully unfunny on social media, and casually accusing a volunteer rescue worker of being a "pedo guy", were more predictive of his future behaviour than were his achievements.

If we think about the predictive value of effort, as opposed to achievement, I believe we will find the same pattern. Effort is likely to be a better indicator of future behaviour. So, when choosing a doctoral candidate, for instance, it might not just be fairer to give someone who has overcome more obstacles preferential acceptance, it might also be a better predictor of success.

"I am, somehow, less interested in the weight and convolutions of Einstein's brain than in the near certainty that people of equal talent have lived and died in cotton fields and sweatshops."

—Steven J Gould "Wide Hats and Narrow Minds

Another pragmatic benefit of levelling the playing field is that people who have the potential to contribute breakthroughs for humanity could be discovered, regardless of their location or situation. In fact Harvard researchers studying inventors and patents in 2018 concluded…

"… there are many "lost Einsteins"–individuals who would have had highly impactful inventions had they been exposed to innovation in childhood—especially among women, minorities, and children from low-income families."—Who becomes an Inventor in America

So, there are both moral and practical reasons for levelling the playing ground to try to enable rewards to reflect efforts.

The way rewards are naturally allocated, align with the general concept of meritocracy, in that achievement is usually rewarded. There is a place for this form of reward, utilitarian benefits are real and valuable, but they are essentially taken care of as a matter of course. But this is not a complete rewards system, it is not fair, and as de Botton states, makes for a society that casts people as "losers" when they may merely be "unfortunate". Michael J. Sandel holds that this creates unhealthy poles in society of hubris and humiliation, because advocates of meritocracy (as it is generally understood) end up misreading achievement as morally deserved.

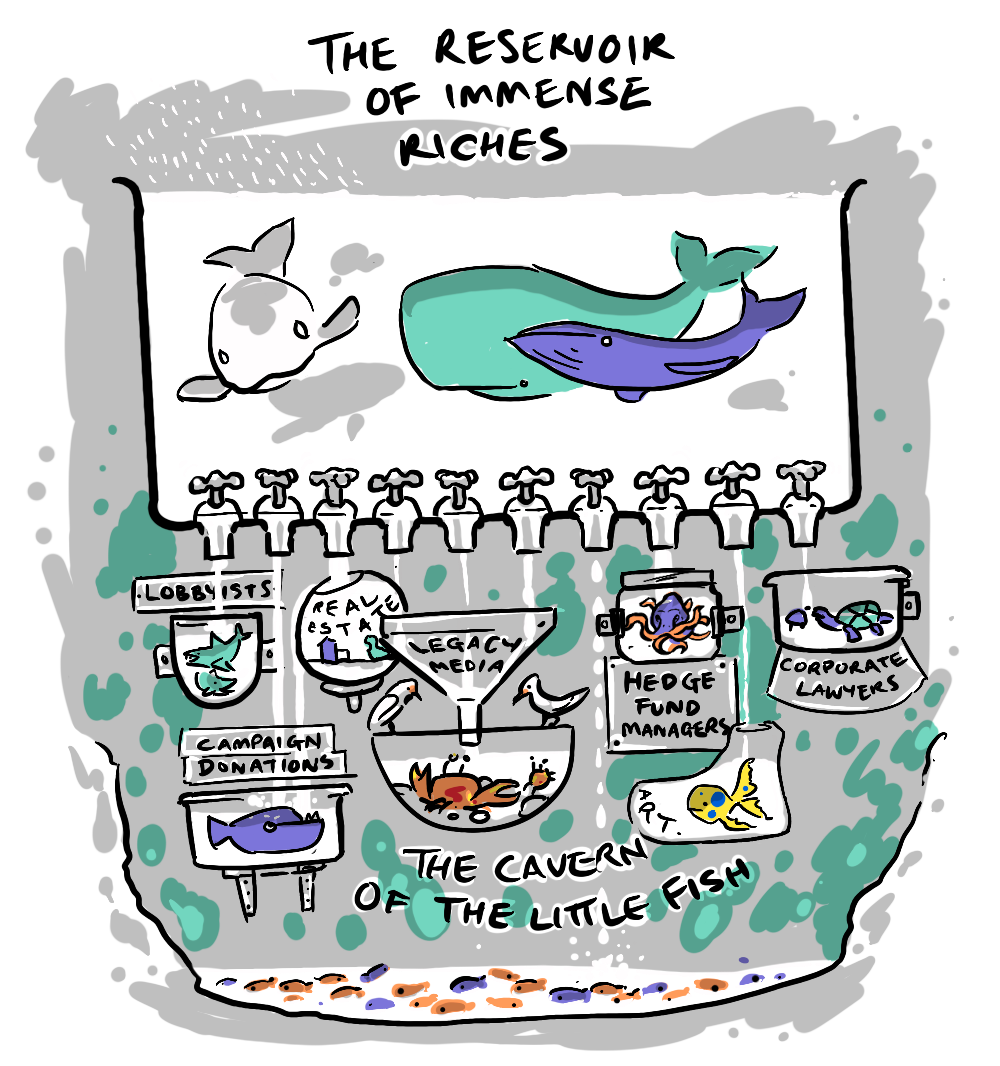

In this way it is as if advocates of meritocracy, are

To truly measure and reward by an effortocratic measure we need both a top-down and bottom-up approach

- At the top, reward people who have overcome more to get to the same point

- At the bottom, level the playing field so that potential, wherever it is, can be realised

I recognise that measuring effort, and levelling the playing field are difficult goals to quantify. We will need to use flawed measures such as outcomes, and personal testimony to record them. And we will need incomplete and distinct categories like childhood development, education, health and finances to try to address them. But this is better than using achievement as the only indicator of merit, or worse as the only indicator of effort.

I believe the meritocracy we actually want is an effortocracy, one that aims at fairness, despite its impossibility. By looking at society as an experiment in levelling the playing field, we are addressing that unresolved question our inner child keeps asking "Why is the world unfair, and does it have to be so unfair?".

And fairness is not all that is at stake. Prioritising effort gives a better indication of future benefits and ultimately leads to discovering the "lost Einsteins" all around the world.

"Imagine how much more advanced society would be today if women, who comprise half the world's brain power, were socially & intellectually enfranchised from the beginning of civilization."

—Neil degrasse Tyson

But most importantly, if you take anything away from this, it is to recognise that if meritocracy is based on achievement only, then we must be sure not to confuse it with effortocracy when it comes to its moral weight. Don't make the same mistake I did in assuming that if something is meritocratic it is somehow fair, and an indication of effort. Recognising what an effortocracy is, makes clear that we very much don't have one, but we can culturally evolve in a way that elevates this value.

An interesting extension of this idea, that goes even further than effort, is John Rawls take on circumstances and effort.

"Even the willingness to make an effort, to try, … is itself dependent upon happy family and social circumstances."

—John Rawls Theory of Justice

While I do think it might be worth drawing the line at effort, Rawls reminds us that we really don't get to choose anything about our initial developmental ingredients, and so should have compassion for ourselves and others, even if it seems like effort is lacking.