This is one of those ideas that constantly recurs in my mind throughout my day, one of those perspective-affecting mental models that helps me navigate the world, and hopefully will do the same for you.

Moths follow one simple rule: in order to move in a straight line, fly at a constant angle to the light. This worked splendidly for millions of years in the moth's evolutionary environment, where their only light source at night was the moon. Because of its distance from earth, as the moth flies, the moon maintains its position relative to the moth—so flying at the same angle relative to the moonlight keeps the moth moving in a straight line. It's a sort of cognitive shortcut provided to the moth by evolution.

But when the light source is a porch light, or worse, a candle, the unfortunate moth, through its biological programming, prioritises the measure of constant-angle-to-the-light as its target…

The result is a spiral into a fiery death.

The moth has, unwittingly, fallen victim to Goodhart's Law.

When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

If there is such a thing as an economic aristocracy, Charles Goodhart is a part of it. Aside from his brother being actual aristocracy (another story), Charles is the great-grandson of Mayer Lehman—one of three brothers who, in 1850, co-founded the investment banking firm Lehman Brothers.

Charles Goodhart is an academic whose publications include tomes with catchy titles like "What Weight Should Be Given to asset prices in the measurement of inflation?" and "Is a less pro-cyclical financial system an achievable goal?"

But Goodhart's claim to fame comes from a simple observation, al-be-it comp-lica-ted-ly word-ed:

So, when we notice a pattern occurring naturally in a system, if we then start to use our knowledge of that pattern to control the system, we end up artificially putting pressure on the system, changing the very conditions that lead to the pattern in the first place. Goodhart realised that simple patterns are vulnerable, in this way, to being gamed (in the same way as evolution gamed moth navigation) and that exploitation of the system can break the pattern or in the case of the moth can render its behaviour fragile to changes in the environment (like candles).

A bit like if—like Biff Tannen in "Back to the Future II"—you travelled back in time with a Grays Sports Almanac and began successfully betting on sports events (knowing all the results), your own behaviour, would eventually start to affect the future in unforeseen ways, eventually even affecting the results of future sporting events in the Almanac.

Or when you're heading to your daughter's dentist appointment, and you get rerouted off the motorway—only to find yourself lost in a warren of gridlocked backstreets, all because everyone's maps software decided to respond to the same traffic pattern in the same way, sending you all down a "shortcut" that couldn't accomodate the influx of cars all at the same time.

We can see already, that while Goodhart's Law was originally an economic principle, its effects are not confined to the marketplace. Think of the way our bodies seek out sugar because, in our evolutionary development, sugar was a psychological measure of vital calories in nutritious vegetation—which is now gamed by processed food manufacturers, at the expense of our health.

Because Goodhart's insight has been so widely useful across so many domains (beyond niche economic circles) the wording has thankfully evolved into the pithy form it takes today—once more…

When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

Another example of Goodhart's Law is one we've all become aware of in the age of social media—the catastrophic results of using the measure of ‘engagement' as a target for social media algorithms—driving conflict and capitalising on negative emotions. Why? Because the algorithms "discovered" a pattern that these were key motivators for engagement—developing, in turn, a shortcut to play to those tendencies, increasing engagement.

The same goes for ‘ratings' in legacy media, generating simple imperatives like:

If it bleeds it leads

Focusing on the measures of ‘engagement' and ‘ratings' has turned out to be at odds with our mental well-being, creating a negative feedback loop, where our worst attributes; aggression, paranoia, a lack of trust and a perspective of hopelessness in each other are amplified by those engagement measures. Our mental well-being, in this case, is what is called an externality .

When we fall victim to Goodhart's Law, by focusing on simplistic measures, externalities are the concerns we fail to take into account—the outside costs, that come back to bite us.

- The moth's navigation system: fails to take into account light sources that are close-by, it's ability to adapt to this is an externality.

- Biff Tannen using the Greys Sports Almanac: introduces the externality of his own success and the effect that has on the spacetime continuum—which would eventually break the predictions of the Almanac †

- The short-cut to the dentist: fails to take into account the fact that everyone has navigation software these days, and what might have worked for one driver doesn't work for everyone all at once.

- Processed foods: the measure of sweetness, being an indicator to of dense calories, essential to the survival of our evolutionary forebears living in a environment characterised by scarcity, fails to take into account the negative health effects of excess, in an environment characterised by abundance.

- Engagement: short-cuts taken by the algorithms to increase engagement fail to take into account mental well-being.

In our everyday lives, Goodhart's Law, and failing to take externalities into account results in a lack of direction, inefficiencies, poor physical and mental health, and sometimes (in the case of the moth) death! But there are even wider implications when we return to…

Being an economic principle, Goodhart's Law also has profound implications through the economy. At the very core of modern economics, the profit motive (a measure of success in business) can lead to cost-cutting measures in the form of low wages, layoffs, or reduced safety, once again at a cost to well-being (an externality), or through the use of cheaper, unsustainable materials at a cost to the environment (another externality).

Many businesses admirably seek to counteract Goodhart's Law with a "triple bottom-line", meaning that not only are they concerned with profit, but also worker well-being and the environmental impacts of their business. But these ethical business practices are largely voluntary, and they require incentives to become common across industries. Those incentives are informed by the wider measures of success at the national level, and in this respect, our modern economy still has a big issue in terms of an overly simplistic measure of prosperity.

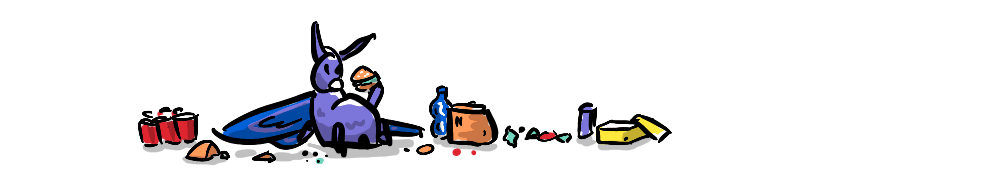

GDP is a single metric that's meant to stand in for, not only various facets of economic prosperity but also standard of living , despite the fact that its key developer; Simon Kuznets had this to say about it:

"the welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measure of national income"—Simon Kuznets

Kuznets didn't think a nation's income would adequately reflect the well-being of its citizens at all.

And in fact in 2008, GDP was at an all-time high, indicating the economy and humanity in general was thriving. But a growth at all costs model (growth being the measure, and costs being any externalities) had led to greater and greater risk-taking—leading inevitably to the financial crisis. And, like a moth to a flame, Lehman Brothers, 158 years after it was founded by Charles Goodhart's Great Grandfather, filed for bankruptcy, poof, it was gone.

As well as businesses employing a "triple bottom-line", there are now a number of new measures being put forward to better reflect real value in the world from the Genuine Progress Indicator to the Gross National Happiness Index . These are multi-faceted measures, and while the concept of Gross National Happiness may sound silly, it speaks to a value above profit, and reminds us that economic prosperity is not actually a primary goal—it is an instrumental goal, a means to an end. Economic well-being after all is only important in as much as it improves… well-being.

Singular goals, whether it's dollars, likes, calories, or a flickering candle, can be seductive, but we are not moths .

Just as there are many opportunities to fall victim to Goodhart's Law in the economy and in our daily lives, be it taking a shortcut, over-eating, arguing online, or disrupting the spacetime continuum, knowing about Goodhart's Law, and the danger of singular goals—and their attendant shortcuts—gives us many opportunities to become aware of our blindspots—those externalities that might ultimately be more important than our immediate goal.

On a personal note, I've recently become aware of how many of my goals are instrumental goals in service of shared well-being—not incidentally, the project of this world-help site. This is a complex goal—it's difficult to measure and perhaps that makes it a worthwhile target. At the same time, as this episode might indicate, aiming too doggedly at this goal might lead to over-thinking , potentially distracting me from being present—which is essential to experiencing well-being in the first place. So, I am trying to remind myself not to let any goals get in the way of moments of enjoyment and connection right now.