"I can calculate the motions of heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people."—Sir Issac Newton

In the previous post we explored the benefits for innovation that reasoning by analogy brings, and the utilisation of this process by the greatest minds throughout history and today.

But is this sort of thinking only available to geniuses capable of holding such vast realms in their minds simultaneously? I don't think so. I think everyone can benefit from these lessons.

We live in a highly specialised world, where it is profitable for each of us to focus on one specific area. In unison with each other, this makes for a highly efficient and productive cooperative network. And yet this specialisation has come at a time when the availability of information has exploded—right when all of human knowledge is available, we are blinkered to it.

And this makes sense, we cannot possibly hope, like J.S Mill, to know everything there is to know. It is overwhelming to think about, and so our default tendency is to pay attention to only that which is immediate, urgent and fleeting.

But analogies don't require us to absorb all human knowledge, they provide for us a way of understanding a topic on a structural level, to "understand" (to stand among) the various components to see how they connect, without having to memorise every detail—a form of information compression*.

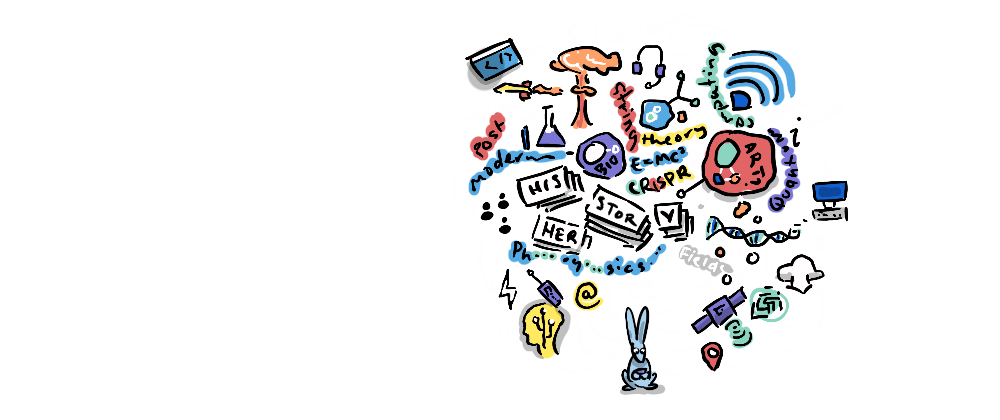

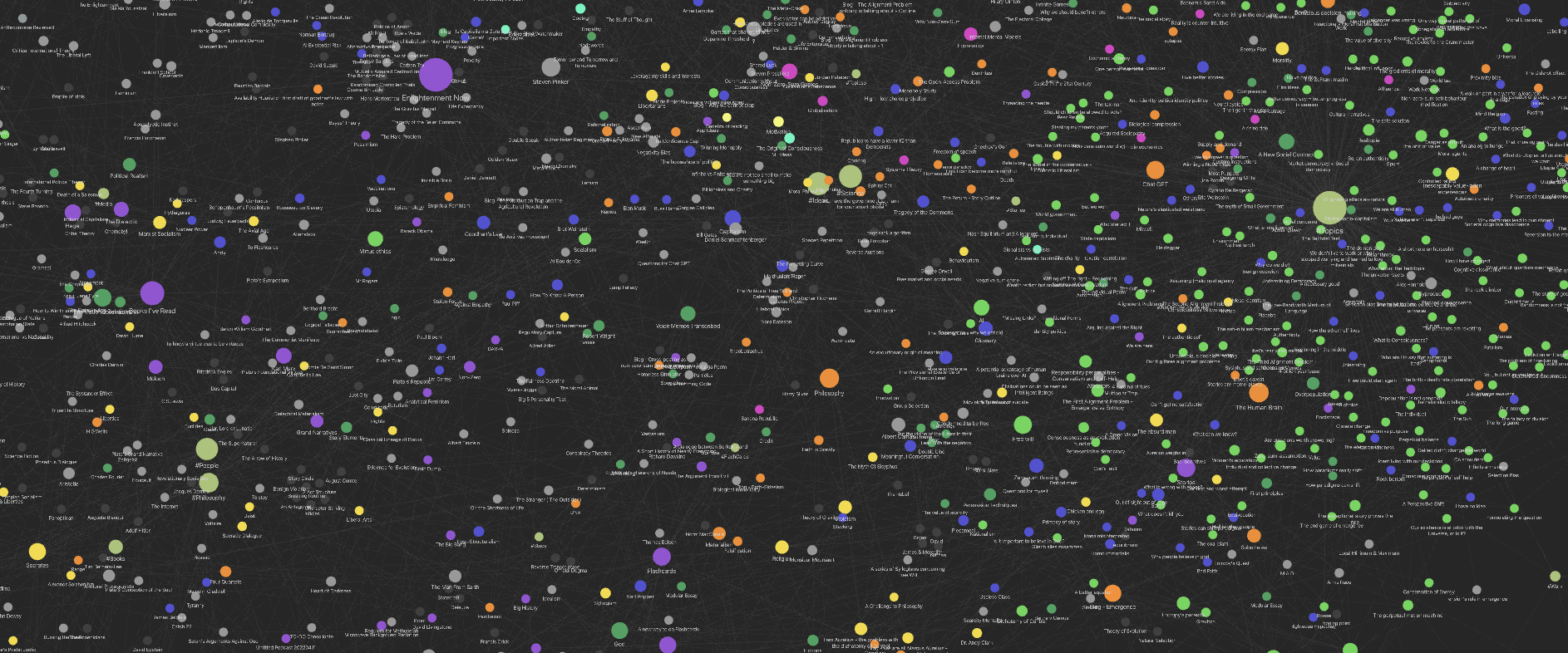

Personally I actively pursue this understanding through making connected notes about ideas that resonate with me. Trusting this "resonance" (re-sonance: the "hearing again" or "echoing") of the ideas is an intuitive sensitivity to the analogous nature of the ideas. When developing posts for the blog, I don't merely set about writing something from start to finish. Almost every post is the result of a new idea coming from an analogy I've recognised between two or more seemingly distinct features of the world†. By connecting my notes in the linked-note-taking app Obsidian, I find myself discovering unexpected connections in a more deliberate way. When I do this, I've found a post topic.

In this post, it was the resonance between polymaths and analogies, and their sometimes complimentary, sometimes antagonistic, relationship to first principles.

This is not only applicable to coming up with original topics for blog posts:

- Lessons I learned in painting, about getting structure down first before detail, I apply to my filmmaking

- Lessons I've learned about story-telling in filmmaking I apply in my blog

- Lessons I learn through writing often apply to my communication as a parent and spouse.

I'm sure you can all think of lessons you've transferred profitably from one area of your life to another (let us know in the comments). But not only are we able to benefit from this, but even geniuses can fail big time when they fail to follow this reasoning. Because reasoning by analogy can be protective, providing a vital sense-check when trying something new.

The polymath Sir Issac Newton found that his genius in mathematics, physics and optics did not transfer to the world of financial investments. As with many other mugs, Newton lost his money in a stock speculation frenzy called the South Sea Bubble of 1720.

"I can calculate the motions of heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people."—Sir Issac Newton

To be fair, in one sense Newton was arguing by analogy in the simplistic way Musk caricatures "this worked, so let's do the same thing again" (arguing by facsimile)—after making a profit selling off an early investment in the South Sea Company, he went on to invest considerably more, which he subsequently lost. But he wasn't intelligently reasoning by analogy here, he was entering a world about which he was ignorant, and assuming he was smart enough to work it out from scratch—more akin to first principles thinking.

In physics, Newton had recognised that systems with three gravitational bodies were not precisely solvable. Had he applied this insight—that adding gravitational bodies destroys predictability (later codified by Henri Poincaré as the three-body problem)—he may have forewarned himself about the unpredictability of a market comprised of thousands of human agents.

Or he could have simply applied the gravitational maxim "What goes up, must come down".

Newton (literally) paid the price for this folly, but this cost was an individual one. As a society, intelligently reasoning by analogy can also act as a crucial safeguard against bad political decisions—decisions that risk consequences for humanity as a whole—despite being made by well-meaning, even highly intelligent individuals.

Elon Musk serves as a contemporary example when he applies first principles to areas outside of his expertise, such as politics and social media.

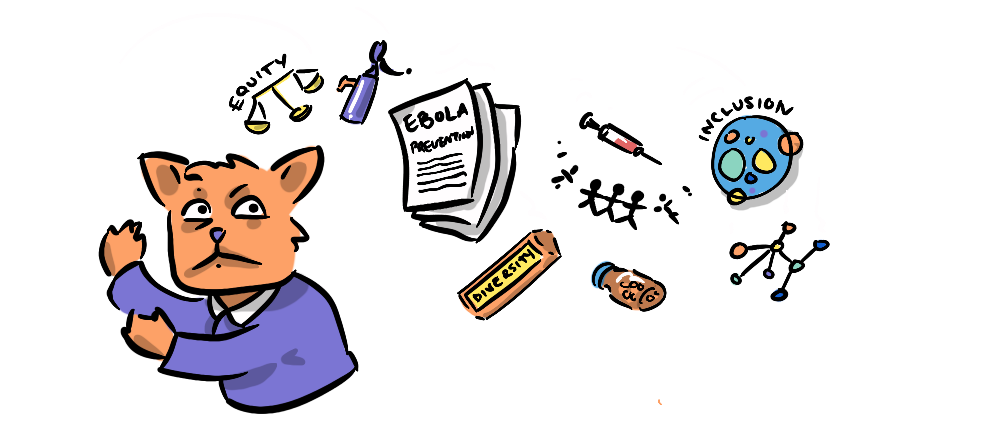

We can understand Musk's reasoning in his approach to slashing funding with the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), as a first principles approach. Having seen the system as irreparably broken, Musk saw radical disruption as preferable to incremental reform. However, eschewing political norms and dismissing bureaucratic guardrails as mere convention, led to chaos in the short term around payments, accidental cancelling of programs like Ebola prevention, followed by deliberate cancellation of critical Ebola prevention contracts, and in the short and long term led to consequences for the lives of millions of the world's most vulnerable. The problem wasn't with questioning the status quo, but dismantling it entirely without an appreciation for what it was providing.

Musk's animosity toward the status quo also ended up blinding him to the intentions of his political partner Donald Trump. Musk found that after cutting costs in the interests of reducing the deficit, Trump introduced a bill that reduced government revenue by 4.5 trillion dollars, dwarfing the savings made by DOGE, driving up the deficit and revealing that Trump's intention all along was to extract money from the poor to further enrich himself.

We see a similar naïveté play out with Musk's foray into social media—entering the fray as a free speech absolutist, Musk has learned the hard way about the pitfalls of absolute freedom of speech online. He has not only had to employ restrictions similar to those held previously at Twitter to comply with national standards, but has also invoked censorship with Grok when he himself became the victim of its slanderous free-tongue.

I would like to think (perhaps naively) that Musk, unlike his political counterpart, has good intentions for humanity, but, like Newton, he has fallen victim to the assumption that genius itself is universally transferable, and that all areas of expertise are reducible to first principles.

Where does that leave us? Well, we've established it's important to recognise that genius in one area does not automatically make someone a genius in another, it is instead the wise application of underlying structures from one domain to another which is important—a polymath goes deep in both areas they are transversing. An unconsidered translation from a field in which you're an expert to a field about which you're largely ignorant, is not guaranteed success.

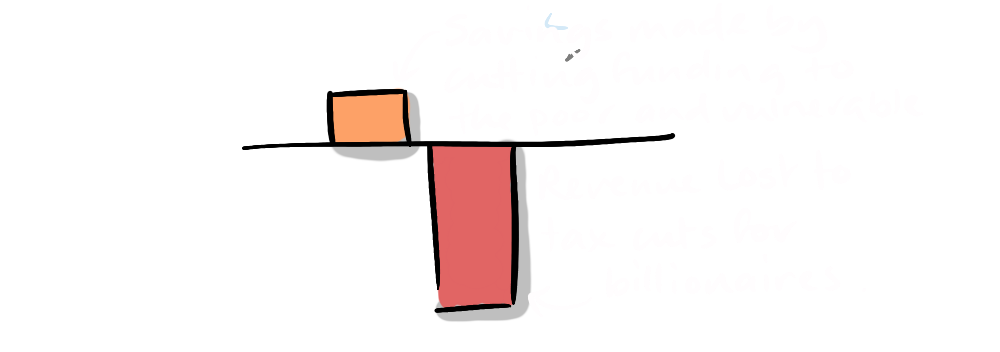

Of course, there are areas where first principles are highly generative, and clinging too closely to familiar patterns can also have negative effects, so we should avoid falling into the trap of copying the surface level of previous behaviour (arguing by facsimile: this worked, so we'll keep doing that), this can stifle innovation, and personal growth. But understanding that the underlying structure of success in one area of your life might translate to another area, can give you the confidence to take a measured risk and try something new.

That's the end for this series, but if you haven't checked these out yet, they're worth a read.