It is easy to hold a double standard where we expect others to take personal responsibility while excusing our own shortfalls. In this essay, I propose that doing the exact opposite. Holding apositive double standardcan help us achieve our personal goals while being more compassionate to others—giving us greater peace of mind.

I have a confession: As a teenager I was desperate to learn how to win friends and influence people , to think and grow rich and develop the habits of highly effective people (seven to be precise)—I am James and I am a self-help-oholic.

These tomes held for me the promise of fame and fortune (though they would earnestly profess otherwise) but most importantly they offered a salve for my crippling shyness.

While I am, today, 20 years self-help-sober, the genre is as popular as ever—with its imperative to stand up straight with your shoulders back (Jordan Peterson), to take extreme ownership (Jocko Willink) and exercise, subtly , the art of not giving a f*ck (Mark Manson).

My

Let’s first look at something they have in common. While not all modern self-help messages are as hyper-masculine as those of Willink, Peterson and Manson, they do all encourage the seemingly uncontroversial virtue of…

The power of ‘personal responsibility’ to positively impact one’s own life has some scientific support. Studies on locus of control , developed by Julian B. Rotter in 1954, found that subjects who believed they could influence life’s outcomes through action, tended to attain…

- Better job satisfaction

- More successful careers

- Better stress management.

Albert Bandura’s research found that individuals who believed in their ability to influence events affecting their lives were more likely to set challenging goals and persist longer in the face of obstacles. Personal responsibility also underpins Carol Dweck’s growth mindset as well as the field of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy .

“Cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) helps individuals to eliminate avoidant and safety-seeking behaviours that prevent self-correction of faulty beliefs” —Mutsuhiro Nakao et al

It was these sorts of findings, touted by self-help books and confirmed by my own early anecdotal experiences, that convinced teenaged-me that we could all be entrepreneurs on a journey of innovation and discovery!

“Meanings are not determined by situations, but we determine ourselves by the meanings we give to situations.” - Alfred Adler

At the time I was unaware, how much I was being influenced by the guiding hand of Alfred Adler.

Famous for coining the term “inferiority complex”, Alfred Adler was initially a collaborator with Freud and a co-founder of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society, although he diverged from the group in 1911—his focus on the individual’s capacity to make conscious choices about their future, was at odds with the Freudian emphasis on unconscious drivers determined by the past.

Adlerian philosophy has been a core influence underlying the self-help genre, from Steven Covey (7 Habits of Highly Effective People) to Brene Brown (Dare to Lead). The genre in general holds that learned optimism over learned helplessness can help people transcend their own situation or baggage—or even to use it as fuel. A recipe for success!

We have explored the benefits of taking personal responsibility on an individual basis. But, a problem arises when the philosophy is applied to society at large. Society is not simply a collection of individuals, it is an emergent phenomenon—a feedback loop between the collective and the individuals that comprise it . This means that statistical predictions can be made about the behaviour of a population based on social norms, pressures or inequities, and no amount of individual will can significantly influence these macroscopic forces.

In this way societies are like…

At the subatomic level, quantum particles, such as electrons, exhibit behaviours that are fundamentally unpredictable. They exist in a superposition—occupying multiple potential positions simultaneously. However, when electrons interact en masse, their collective behaviour becomes entirely predictable— order out of chaos .

Groups of human individuals exhibit this same statistical predictability. A simple example is the sex ratio; we can’t predict what sex a baby will be at conception, but it is statistically predictable that for every 100 girls born there will be 105 boys . We can also make statistical predictions about human behaviour based on changes in the social and physical environment. While a given individual being unemployed doesn’t predict that they will turn to crime, lower unemployment is predictive of lower crime rates and while vaccination doesn’t guarantee individual immunity to a virus, vaccination rates are predictably tied to lower disease incidence . Humans may be unpredictable, but groups of humans are subject to predictable statistical realities.

Groups of human individuals exhibit this same statistical predictability. A simple example is the sex ratio; we can’t predict what sex a baby will be at conception, but it is statistically predictable that for every 100 girls born there will be 105 boys . We can also make statistical predictions about human behaviour based on changes in the social and physical environment. While a given individual being unemployed doesn’t predict that they will turn to crime, lower unemployment is predictive of lower crime rates and while vaccination doesn’t guarantee individual immunity to a virus, vaccination rates are predictably tied to lower disease incidence . Humans may be unpredictable, but groups of humans are subject to predictable statistical realities.

So, does this mean that we don’t have any personal control, and therefore no personal responsibility?

Not necessarily, it merely means we can’t expect everyone else to have just read the same self-help book we’ve just read, and to have come to the same conclusions we have, and to be implementing those new behaviours

Self-improvement is an epic quest requiring a lot of factors to align; you need to realise you have an issue, you need to be motivated, you need to have time to research and devise new behaviours, you need freedom from obligations that stand in the way and even with all those factors aligned, it’s just hard to change. It’s much easier to expect others to change.

“It is always easier to fight for one’s principles than to live up to them.” — Alfred Adler

This is the crux of the problem. An individual who is on a self-improvement journey and is maybe even successfully employing a philosophy of ‘personal responsibility’ can easily assume a political philosophy of ‘personal responsibility’—one that discounts systemic inequities and puts the blame for the fortune of entire demographics on the individuals within them.

Politicians who enlist ‘personal responsibility’ as a talking point, do so under an assumption that we live in a meritocracy, or even if they concede that “life is unfair” there’s an implication that life is somehow equally unfair…

This brand of politics holds that society doesn’t owe us anything, but fails to appreciate that part of not expecting anything from society means not expecting that every person can always be the best version of themselves, even if you might personally be going through a period of self-improvement. And given that self-improvement on an individual level is so difficult, expecting change from entire populations without social reform is… naive, especially given the data.

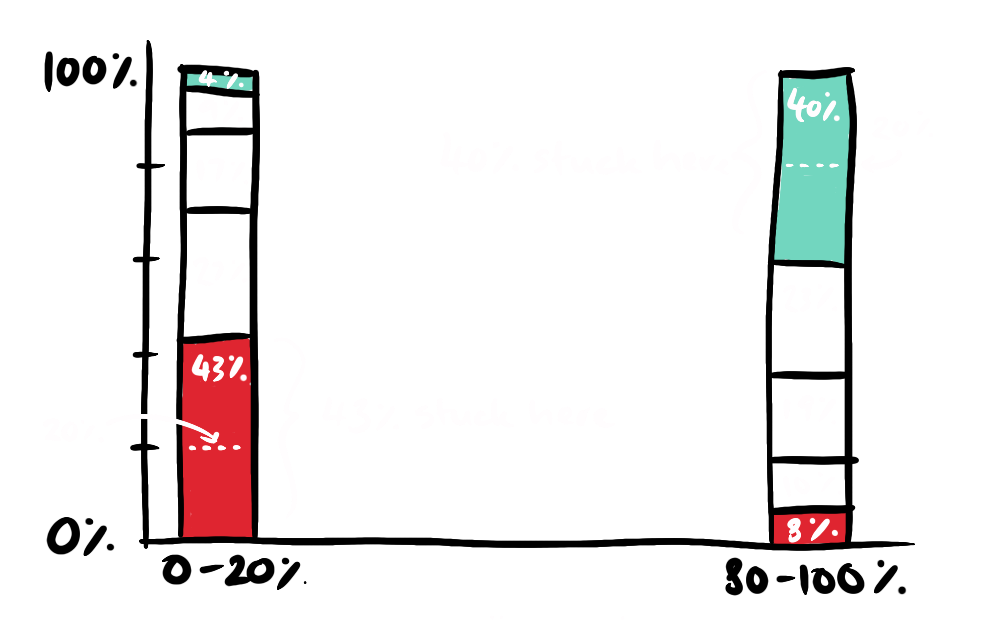

SOCIAL MOBILITY In the US the correlation between a parent’s income and their children’s future income is around 50%. Were we to live in a meritocracy, where effort was the only factor in success, children born into the bottom 20% of incomes, would have the same chance of being there in adulthood—20%. However, Pew Research showed in 2012 that the children of income earners in the bottom 20% have a 43% chance of remaining there. The same is true of the top 20%, who have a 40% chance of staying there. The results are magnified when race is taken into account.

While human beings aren’t numbers, statistics do represent real individuals. Being stuck in that bottom 20% is a mother deciding between putting fuel in her car so she can get to work or feeding her kids, it’s about instability—a father doing everything right but knowing that a simple illness, and a missed shift could domino out of control. All this is exacerbated by the stigma and judgment that is projected onto someone in poverty, when their misfortune is seen as a moral failure—or as Margaret Thatcher put it…

… a personality defect.

But these statistical realities are a product, not of individual choices but of policy—policies have predictable statistical implications . While taking personal responsibility for your own future can help you as an individual, inequality cannot be addressed by demanding ‘personal responsibility’ for every individual member in a population.

That’s not how statistics work, it’s not even how ‘personal responsibility’ works.

It is the individual who is not interested in his fellow men who has the greatest difficulties in life and provides the greatest injury to others. It is from among such individuals that all human failures spring.— Alfred Adler

As I interrogated this issue, I could see that the individual philosophy of personal responsibility that helped me succeed and become more confident, had, in the wider world warped into a political ideology that denigrates whole populations facing systemic disadvantages—advocating against the very policies that would level the playing field (the only way to achieve meritocracy). The elixir of individual achievement (personal responsibility) turns out to be delivered in a poisoned chalice (individualistic politics) collectively—how can we overcome this paradox? Re-enter our hero, Alfred.

A key element of Adler’s philosophy was lost in his influence on the self-help genre—his concept of “Gemeinschaftsgefühl”. Encapsulated in typical German philosophic style with this compound word meaning “Community Feeling”. The idea was that genuine individual well-being could not be achieved without developing a sense of solidarity and connectedness with the world and everyone in it.

His position was that we can determine our future through our choices, but we must also contribute to the community feeling we want.

“The important thing is to develop the courage to move forward, to dare, to stop being anxious, to look ahead with joy and see one’s fellow human beings in a friendly light.”— Alfred Adler

Adler’s philosophy provides both a cause to the problem at the heart of self-help (an overemphasis on personal responsibility) and a solution to it (a compassion for community). This is why I’ve resolved to hold a…

A positive double standard requires that I take personal responsibility while not expecting the same of society. This position holds that we have the power to change our own individual futures, but recognises the statistical realities of social dynamics on populations.

Change is hard, and the efforts others make to change are often invisible to us. Adler suggests that we should believe in our own ability to make the most of our own potential while having compassion for and contributing to society. In this way it is important to employ a positive double standard.

This is not to say that we should assume we are superior to others in society, we’re merely seeking to recognise that there are social dynamics at play for all of us. I believe this is a realistic outlook, and find it helps me personally to understand my own journey and issues in society a little better—seeing my fellow human beings in a more friendly light (even those with political ideologies with which I disagree).

The imperative to take personal responsibility sits on the free-will end of the determinism spectrum, setting the locus of control within us. A determinist might dismiss this sense of personal agency as not fitting with their view of the world, and I don’t mean to bicker with them about this. Whether it is true or not that we are free to determine our own futures, the science suggests it is productive to believe that, individually, we can.

On the other hand, someone who believes we have free will, and are truly masters of our own fate, might argue that it is right to demand personal responsibility of the masses, but as we have seen, science suggests that even if we have free will, statistically it’s productive to act as if populations don’t, because the behaviour of populations is relatively predictable.

What do you think?