Would you believe this painting is worth $186 million?! I certainly didn't at first glance—that is, until I understood the game theory behind it.

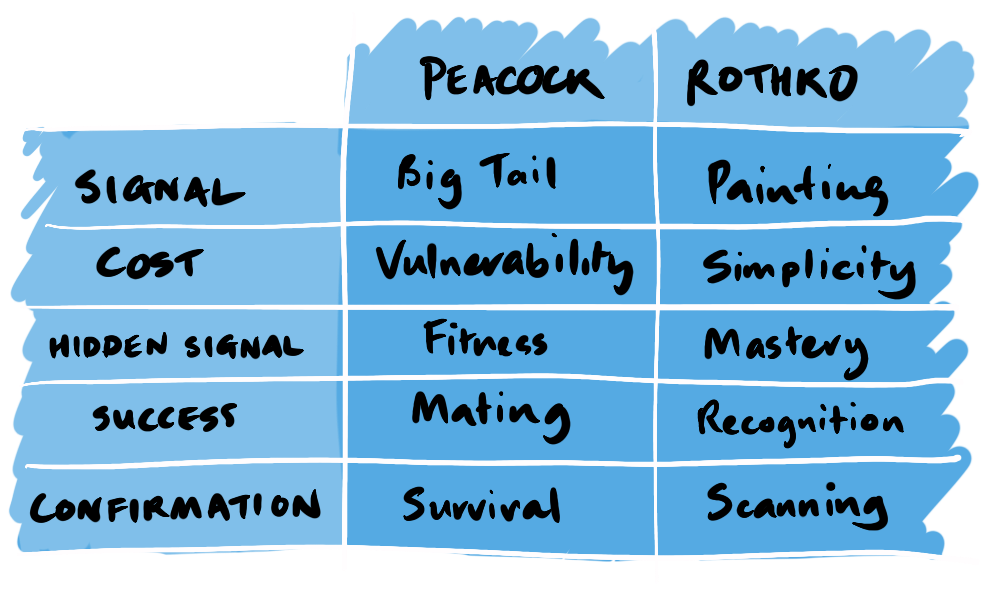

We all see 3 rectangles. However, our appreciation for the artist's intentions, efforts, and expertise greatly differ. If you're an art aficionado, you probably appreciate the hours of effort behind Rothko's self-prepared, modified oil paints—egg, glue and damar resins to create a layered texture as well as phenol formaldehyde to prevent layers blending into each other. If you're an art novice like me, you probably just found the colour contrast cool. But if you were MIT economists Erez Yoelli or Moshe Hoffman, you would see Game Theory hidden amidst the textured layers of this canvas. Yoeli and Hoffman explain Rothko's "buried signals" of artistic prowess through a phenomenon called Costly Signalling. Their example? Peacock tails.

In this game between signal senders (peacocks) and receivers (peahens), there are two types of senders. A "high type" (good genes) and "low type" (poor genes). The peahen doesn't know the type, receiving only signals—long, beautiful tails. There are two key conditions:

- Signals are costly (they increase predation risk by slowing down movement and increasing visibility)

- Signals are less costly for high types relative to their fitness (superior genetics allowing survival even with longer tails)

The peahen's Nash Equilibrium strategy is to mate with long-tailed peacocks—increasing their chance of mating with a high type. An interesting consideration here for the peacocks' signals is balancing the trade-off between predatory risk and mating success (this balancing being done the old-fashioned way via natural selection).

I know what you're thinking—how on earth is any of this related to Rothko? Isn't it the exact opposite of what he's doing—burying "signals"? Not quite. Recall the two conditions: signals must be costly, and less costly for more desirable senders relative to their fitness. Here, mastery is what is being signalled by virtue of its hidden nature—a signal that one can afford it going unrecognized.

Why is it less costly for artists like Rothko to send such a signal than amateurs, and how is it a Nash Equilibrium strategy? Here's where Yoelli and Hoffman's conditions come in, masterfully explaining human "modesty."

CONDITIONS

- The sender has so many positive signals, they're sure one will come up without explicitly mentioning it—doesn't apply here.

- The idea of repeated interactions that I've explored extensively before—if the signal isn't understood today, it probably will be tomorrow. This nicely explains modesty on a first date when the next one's in a week—but again, not applicable here.

- The sender has devoted fans. This is highly relevant to Rothko's buried signals—his experimentation with color field painting only began in his career's final stages, after he was well-known. When buried mastery is uncovered, as it was in Rothko's case when the Italian company MOLAB used mass spectrometry and electron microscopy to understand his layered paintings, it confirms a signal of status. Scientific laboratories to analyze a painting? Now that's devotion, and a clear sign of expertise.

- Finally, and perhaps most importantly, specific observers. Rothko's target audience wasn't the general public. He was more focused on art critics and connoisseurs such as The Ten, a group of expressionists like Rothko who held joint exhibitions. Rothko didn't seek widespread recognition, even "hating" the fame and encouraging his viewers to find the tragedy, the "utter violence in every inch" of his paintings instead of making them collectibles. He wasn't after money or fame, but wanted to invoke true emotion in his expert audience.

Since Rothko meets the final 2 conditions, we now understand why he's playing a Nash Equilibrium strategy by burying signals. The benefits of being recognized for burying mastery outweigh the costs of going unrecognized, because of devoted fans and specific observers. As for signal-receivers, "accepting" Rothko (just as the peahens accepted the peacocks) after recognizing the buried signal is undoubtedly Nash—someone who isn't showing off greatness but possesses mastery? That's exactly what groups like The Ten and art connoisseurs desire.

This idea isn't just applicable to Rothko's mastery. Ever wonder why, in some parts of South Asia, growing a long pinky nail is considered "beautiful" despite Western culture unanimously disagreeing? Another costly signal, as Yoelli and Hoffman explained, of being rich enough to avoid manual labour, which is impossible with the nail. It's been internalized so deeply into their psyche over generations, they now simply deem it beautiful.

I'd highly recommend giving Hidden Games a read if you found this piece interesting—the examples and concepts they unpack truly do explain irrational human behavior!